Taking stock, making change

ALSO: Coffee shops point to slight office recovery / No quotas seem to work best

What the last fifteen months has done is force an intervention on us. It’s asked us to take stock of the way we were working. Over the weekend I was listening to a TED Talks podcast about stress at work. The two contributors, Emily and Amelia Nagoski, casually described coping with levels of workplace stress that were so extreme that if we hadn’t taken collective leave of our senses we wouldn’t be asking ‘how can we learn to cope with this?’ but rather ‘why on earth would anyone permit jobs with this level of stress to continue?’

Many of us have witnessed a version of work that is relentlessly demanding and overwhelming. The detail in the report by the World Health Organisation last week gave a stark warning that overwork is killing us. If you work more than 55 hours a week you have a 35% increase in your likelihood of having a stroke and 17% increase in developing heart disease. As I’ve said before other measures of stress tell us that stressful jobs kill us - junior doctors who clocked up an average of 65 hours work a week saw their bodies age 6 times faster than normal. Over work doesn’t accelerate our careers it hastens our demise.

Worse still, the elements of our jobs that used to mitigate some of this - the humour, the camaraderie, the autonomy to feel challenged - have been gradually eroded by robotic leaders who have valued compliance over imagination when they’ve seen the demands upon them increase. Great workplace culture used to be about working alongside intelligent, witty, creative colleagues or co-workers who had the scope in their jobs to delight customers. When you’re around people who can inspire or surprise you it makes for a wonderfully fulfilling working environment. This isn’t an invention, Wharton professor Sigale Barsade has measured that ‘companionate love’ results in workers feeling more productive and more accountable.

The unspoken fact is that over the last decade working was becoming increasingly disagreeable for most people. Open-plan offices left us unable to get anything done in the office. (Aside, here’s Rory Sutherland on open plan offices this week). We’d find ourselves hiding in meeting rooms dreading someone who had booked it turning up and turfing us out. Constant connectivity has meant that the average working day has increased by two hours in the last decade.

Rather than address this by working differently firms who were advantaged with resources changed the subject of debate. The way that great culture was pitched to the outside world became about what benefits the firm provided - gym membership, subscriptions to the Calm app, free food or snacks - none of these correlated with a motivated workforce - or a stimulating work environment but alongside Instagrammable office scenes it made it look like you’d landed a job your friends would be envious of. Led by venture capital funded firms in the US some companies consciously even set out to blur the lines between work life and home life because it ended up with employees working longer.

The battlefront of looking like your firm cares has continued to evolve. Recently I’ve heard companies announce initiatives like ‘mindful minutes’ - where everyone would sit for an awkward 60 seconds of silence before their meeting. Sixty eternal seconds where every part of your being is screaming ‘I’ve got a full inbox, what the hell is this about?’ or ‘I don’t even know why I’m in this meeting, who are these people?’

When work is so stressfully disagreeable it’s no wonder initiatives like Mental Health Awareness week are perceived so cynically. As comedian Ania Magliano says ‘it’s okay not be okay (as long as you’re contactable by email’.

On the employer review site Glassdoor, a good workplace culture is regarded as more important than salary for most prospective employees.

So hopefully the last 15 months have given us scope for us to pause and take stock. In 2010 Rebecca Solnit wrote a powerful book studying disasters - and the impact they have on the people affected by them. Whether natural disasters like the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 or Hurricane Katrina, or manmade calamities like 9/11. She believes our prior expectation of the aftermath of disaster is mass panic - screaming people running in all directions with arms waving like the inflatable man at American car dealerships. She explains that mass panic is in fact a trope that principally comes to us from disaster movies. In reality disaster is normally followed by a groundswell of community thinking. Old society, laden with divisive, conflicting identities is torn down and ‘in its place appears a reversion to improvised, collaborative, cooperative and local society.’

Solnit shares wonderful stories of altruism and inventiveness. The word that lives through all of the experiences is improvisation. With no answers people get to work inventing solutions to the challenges that present themselves - and prove themselves fabulously capable. It’s no wonder that repeatedly people describe that they missed the world that briefly existed after the storm.

‘In the moment of disaster, the old order no longer exists and people improvise rescues, shelters and communities. Thereafter, a struggle takes place over whether the old order with all its shortcomings and injustices will be reimposed or a new one, perhaps more oppressive or perhaps more just and free, like the disaster utopia, will arise.’

Solnit’s stories hit home because improvisation was very much the spirit of the first part of lockdown last year. When we went into the improvised, disaster recovery mode workplace engagement went up. When workers were asked to come up with answers, they loved it. Over the last twelve months we’ve deleted that memory and gone back to something more stressful, more top down.

After the end of Mental Health Awareness week we might reflect that the reason we never used to have these things is because we didn’t need them to the same extent. Work was never this unsustainably stressful.

With the widespread adoption of hybrid working there is a critical opportunity for firms to make a decision here. Can we learn that workers freed from the restrictive demands of top down management feel more able to get more done? Can we reallocate resources to make work more focussed on outcome and less on supervision? As Gary Hamel told me a few months ago, a third of the workforce is now bureaucratic middle managers , merely sustaining a reporting pyramid that we could remove with no cost. How much more motivated would workers be if they were freed from reporting - and given more autonomy to do their jobs?

As we approach the summer, it’s on all of us to reflect on whether there are lessons that we can learn to reform our workplace cultures - to create better versions of our jobs.

Related: Charlie Warzel asked people what they’d like to see companies do to help them recharge this summer. The answer: summer Fridays, time off, time off, time off (scroll down for the answers)

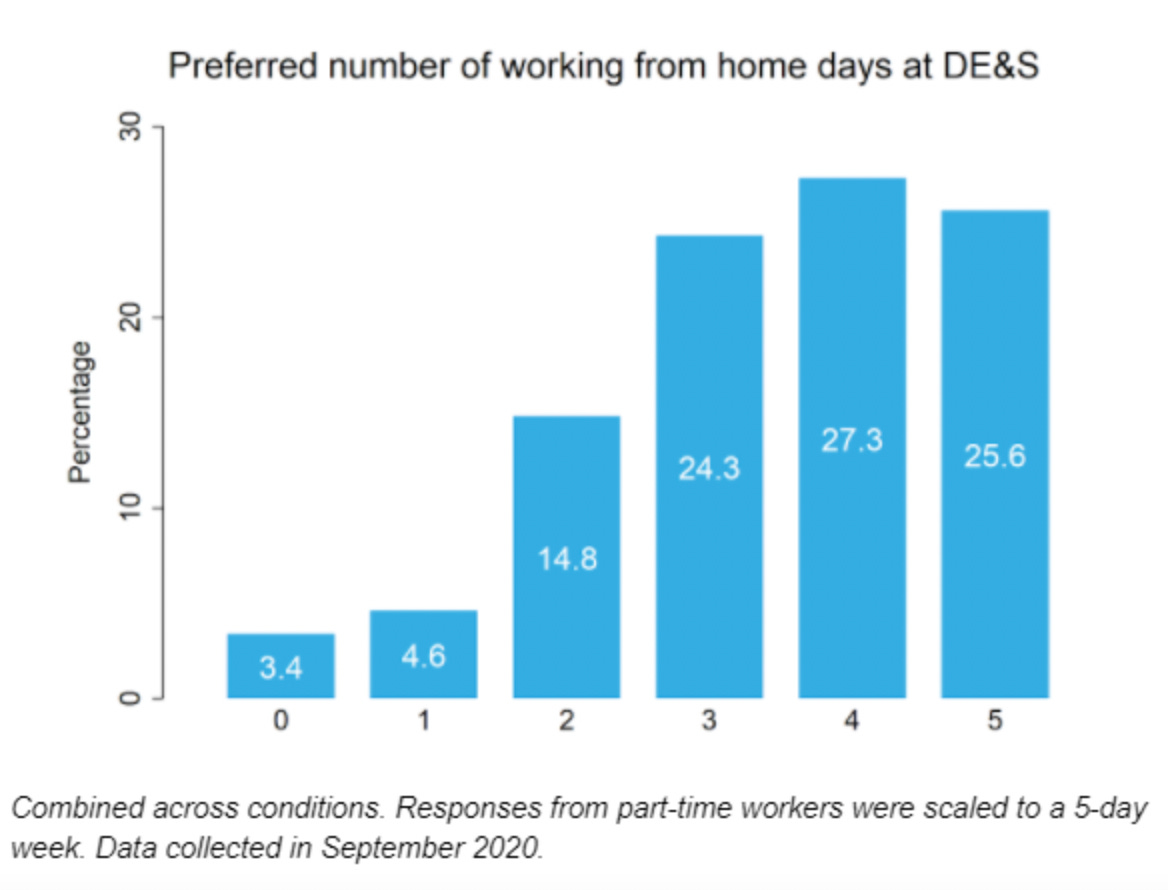

Creating expectations of office working tends to reduce homeworking from the preferred levels

The UK government’s Behavioural Insights team looked at the preferences of hybrid working in their organisation. They discovered that across 3852 employees the vast majority of employees wanted to work either 3, 4 or 5 days at home. The department, that is responsible for looking at nudges that might gently move attitudes and behaviours found that when a recommended number of days in the office was suggested women were inclined to reduce their preference for time at home (in contrast men didn’t change their opinion). As a result of this the DE&S is looking to create a policy ‘without imposing quotas’. Read the report.

I was intrigued to see someone using Microsoft’s MyAnalytics posted this -

Will be intriguing to see if these nudges reduce meeting size and change behaviour over time, or if they just become Clippy style annoyances.

If you find exercise helps you deal with a stressful job then it might be best to do it before work rather than after - stressful days at work leave us less likely to exercise

In a survey of marketing firms 28% of workers said they’d not heard from their employers about what their return to offices plan was

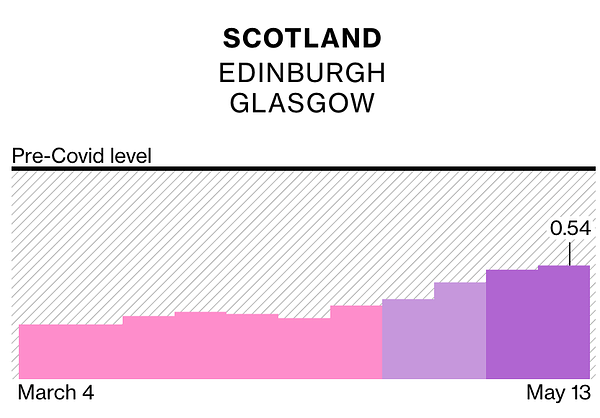

Remarkable numbers: a quarter of UK firms to close or downsize offices (I’d love someone to explain to me how can this won’t blow up the property market?)

Brene Brown featured a return of Priya Parker on her podcast this week. Priya wrote a book about the glory of meeting up and she discusses some of how we should be thinking about returning to face-to-face gatherings. Caution there is a lot of fluff in this podcast and I’d suggest you start at 45 mins remaining (Brene Brown’s style on these podcast is baffling to me, like someone on their phone trying to follow a Netflix show)

#MeToo: Don’t mess with Melinda Gates’ lawyers, they’ve spent 2 years gathering receipts on some highly toxic behaviour

WeWork’s customers dropped from 693,000 to 490,00 and the business filed a quarterly loss of $2.1 billion but surely things are about to pick up for the company?

Thanks to Tom Kegode for the Ania Magliano TikTok - Put his Beatz Friction show on while you’re working for extra flavour while you’ve powering through emails.

Main photo by Jong Marshes on Unsplash