A survival guide to creating energised cultures when politicians are screaming at you to get back to your desk.

'They edited it to make it look like I was slumped at my desk'

Last month marked 21 years since the end of the first series of Big Brother on Channel 4 in the UK. In that time audiences’ understanding of Reality TV has developed and matured from the wide-eyed excitement it was first greeted with. Big Brother was initially presented as a psychological experiment, complete with a documentary episode on a Sunday analysing the body language and behaviours of the participants. But before long we began to understand that TV producers would create plot-lines for the characters that would shape the content they showed to us. Events were edited to make life seem significantly less boring. Archetypes would be created for the participants (Nicola is argumentative, Brian is extra, etc) and clips found to substantiate those roles. ‘They edited it to make me look bad,’ contestants soon took to telling us.

Over the last year certain leaders have repeated this staging exercise when it comes to talking about the office. There’s been re-editing of the highlights that has bordered on gas lighting, trying to make out our workplaces are the answer to our creative slump. ‘The office is a hub for creativity’, read one recent headline in City AM. Elsewhere architects have been called on to champion the role of ‘creativity through office design’. It’s as if someone microwaving fish every day never happened.

To many of us these descriptions of the idealised version of work don’t seem to be consistent with what our experiences really were. If we listen to the stories we’re hearing the office were incredible citadels of happiness and free thinking: The office was a place of non-stop conversation, a place ringing with the sound of laughter, filled with banter, the office was a place of zingy imaginative thought.

Of course, the office could be all of those things but it often wasn’t and it most certainly wasn’t the default home for new ideas. We’re trying to portray a character in our reality show based on behaviours that we’re struggling to find in the highlights reel. Back when we found ourselves mainly based in the office commentators were more likely to decry its harmful effects on our creativity than suggest we’d find our inspiration there.

We should be honest because if we’re trying to sell an office-based version of hybrid working by saying ‘it was the place that we came to be creative’ then we’re destined to fail. It simply wasn’t.

There are some things that the office was decidedly strong at. It could be a place of team cohesion, a place where we felt a sense of togetherness that could have an effect even in a gentle way. It was a place where we felt part of something, part of an ‘us’.

In her book The Lonely Century Noreena Hertz tells that even tiny acts of engaging with each other can make us feel happier and in aggregate these actions can forge a sense of togetherness.

Of course it does beg the question of how often do we need to come together to feel part of a congregation? Most major religions settled on once a week for the keenest, or a couple of times a month for most. I’m very interested in the experiments that different firms are trying, here one company called The Foundation has hit upon ‘Wednesday +1’ as their solution. Wednesday to foster togetherness, +1 to ensure that the office isn’t deserted for those who want to work in it.

It’s the idea that our offices were a place of creativity that is the most dangerous fable for us to propagate. Most of us worked in open plan environments that were characterised with frustrating interruptions and very low employee satisfaction scores. The truth about creativity is that it tends to thrive only when we create space for it. If we allow creativity to be stressed or squeezed it withers. Telling yourself that your team need to be back in the office to be creative is a myth which when it proves to be untrue might add to one of the nails in your ‘return to the workplace’ experiment. My favourite story on the route to inventive comes from the origin story of graphene.

When I read Vivek Wadwha’s book about future technology a couple of years ago his prediction that in the long-term we will subscribe to electricity in the manner of our phone contracts (with no limit to what we use each month) seemed fanciful and ridiculous. Now it seems inevitable to me. The only barrier to us resolving climate change right now is our implementation of cheaper technology that already exists. Extrapolate that two decades and you get to ‘all you can eat’ power - as crazy as that idea seems today.

Alongside that we’re still discovering technology that is yet to be implemented. Graphene was in the news again a couple of weeks ago and certainly sits in that category. The wonder material is a layer of carbon a single atom thick that is so thin it is sometimes described as two dimensional. It’s thinness, while rendering it nearly transparent, isn’t at the expense of strength, a sheet of graphene is 200 times stronger than steel and it’s regarded as the strongest substance ever discovered. It’s so thin that a single gram of the material can cover 700 square metres. Graphene conducts electricity, can be used to filter the salt out of sea water and is expected to be used to create batteries that can be charged five times faster than those we use today.

But the origin story is the lesson for us when it comes to understanding creativity. The two scientists who first isolated it, now Sir Andre Geim and Sir Konstantin Novoselov, were professors from University of Manchester who ended up scooping the Nobel Prize for Physics for their work. Geim and Novoselov had found that in a normal working week there was no space for creativity. In their case it got squeezed out by teaching, emails and the delivery of the terms of the grants they had received. The pair felt the joy slipping from their jobs and set about taking action ot resolve the situation. They set aside an informal ‘Friday-night experiment’ slot. Every Friday afternoon they’d set aside two or three hours to do what they didn’t have time for in the normal working week. And so determined were they to bring the fun back to their job that they set themselves clear rules of what constituted acceptable experiments.

And it was in this carefully protected space set aside for creative play that they found their breakthrough. Preposterously the pair won a Nobel Prize for an experiment they conducted using sticky tape and pencil lead. Using a thin block of graphite as their start point they realised they could remove a tiny layer of it by the repeated application and removal of the tape. Apply the tape enough and thin block of carbon became shrinkingly thin. Like Rick Rubins’ work on Yeezus, Geim and Novoselov didn’t produce graphene, they reduced it.

This is a common finding when it comes to creativity. Creativity thrives when we set time and space aside to create. It rarely just happens and there’s no proof at all that it merely happens as a chance encounter in the hallways of our offices. As we set about painting our visions of the work to come it won’t suit any of us to paint the office with attributes it doesn’t have. Like trying to paint a reality contestant a certain way and finding that we have no clips to prove it. Telling our teams that our workplaces are like magical Narnia-like kingdoms, home to imaginative thought it a red herring. Office fanatics can make their case, but creativity isn’t it.

Our firm went remote first - ask us anything - over the last few weeks I’ve been intrigued with the firms who have chosen to bite the bullet and ditch their office. What are their philosophies about getting colleagues together in person? How do they think about recruiting? What software tools do they use? What made them make the leap?

I chatted to Camilla Boyer at Hopin, Andrew McNeile at Thinscale, Lewis Clark at Qatalog, Lisa Freshwater at Blood Cancer UK and Dan Sodergren at YourFLOCK.

Listen: Apple / Spotify / website

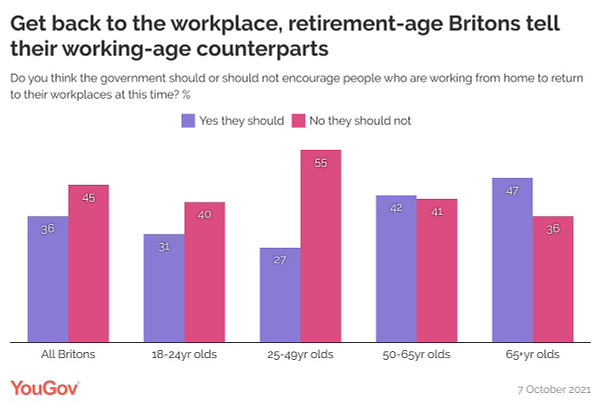

YouGov’s report (above) that pensioners are keenest to see workers go back to offices was quickly followed with Iain Duncan-Smith’s invocation of the Blitz spirit as a reason to return. It’s over twelve months since the return to the office was first used a culture war and it’s the headline that keeps creating rage-on-demand for the people it’s targeted to annoy

12 questions about hybrid work - answered - I struggle to think of any firm I’ve spoken to in the last 12 months that isn’t integrating some degree of flexible working. As a consequence this Harvard Business Review piece providing a checklist of remote working is essential reading. Their checklist includes:

What’s the best way to approach hybrid work designs?

How do we ensure that proximity bias doesn’t affect career advancement?

How do we measure the performance of remote or hybrid employees?

How can we foster trust among teammates who seldom see one another in person?

How can we eliminate tech exhaustion?

How do we match digital tools with work needs?

How should leaders rethink office spaces for in-person work?

What are best practices for remote onboarding? (The article is well twinned with this checklist from Harvard professor Tsedal Neeley)

HSBC’s CEO says ‘forcing staff back to the office would be a betrayal of trust’ - as they plan to cut the office size by 40%

Last week within a day I heard one firm tell me, 'we’ve decided we’re going to do a hybrid trial, but it we’re sure it won’t work and we’ll ask everyone back full-time from January’. The same day I heard that the boss of a very traditional organisation where (due to location) most workers commute for 2 hours every day has already decided to bring workers back as soon as possible - despite the workers loving the work/life harmony of their realigned lives. Meanwhile the same day PwC announced all of their staff can work remotely forever. If these firms don’t believe they operate in a single job market then it’s only going to take a few additional firms before they start to learn. Insert your own Chemical Ali ‘nothing to see here’ meme

I always enjoy Caleb Parker’s podcast WorkBold - which takes a commercial real estate perspective of the changes happening in work. There have been some good highlights this season but I really enjoyed the final episode which featured a discussion about how hotels and offices are increasingly in adjacent spaces

‘Big tech companies are at war with employees over remote work’ - 68% of Apple employees felt that lack of flexibility would force them to leave the company

‘I am not anti-office. I am anti arbitrary office. I am against sucking two hours out of someone’s day just to briefly make a bad manager feel good’ - Anne Helen Petersen on why we might be heading towards ‘the worst of both worlds’

Senior ad-man Rishad Tobaccowala has suggested that we need to think about work as split between four location-based modes with less than a third of the year spent in the legacy office. Time will be spend between: 1) home 2) outside of home pods 3) periodic events/experiences 4) the legacy office

If you liked this, please share it, spread a little love. Make Work Better is created by Bruce Daisley, workplace culture enthusiast. You can find more about Bruce’s book, podcast and writing at the Eat Sleep Work Repeat website. This week I’ve been obsessively zipping through Duolingo’s Arabic course.