Is your toxic culture driving employees away?

And can toxic culture be fixed? We look at the Met Police

One of the themes that has emerged from the discussions of the Great Resignation is the role that toxic workplace culture is playing as a motivator to quit a job. In a major analysis published just a couple of months ago a team led by an academic from MIT Sloan took a look at a vast number of employee resignations to understand what motivated workers to make a move. Having first identified the firms that had higher quit rates than their sector benchmark they analysed the Glassdoor reviews for those organisations to see if any key descriptions stood out. The findings are fascinating.

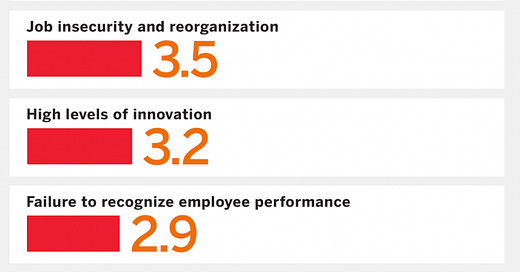

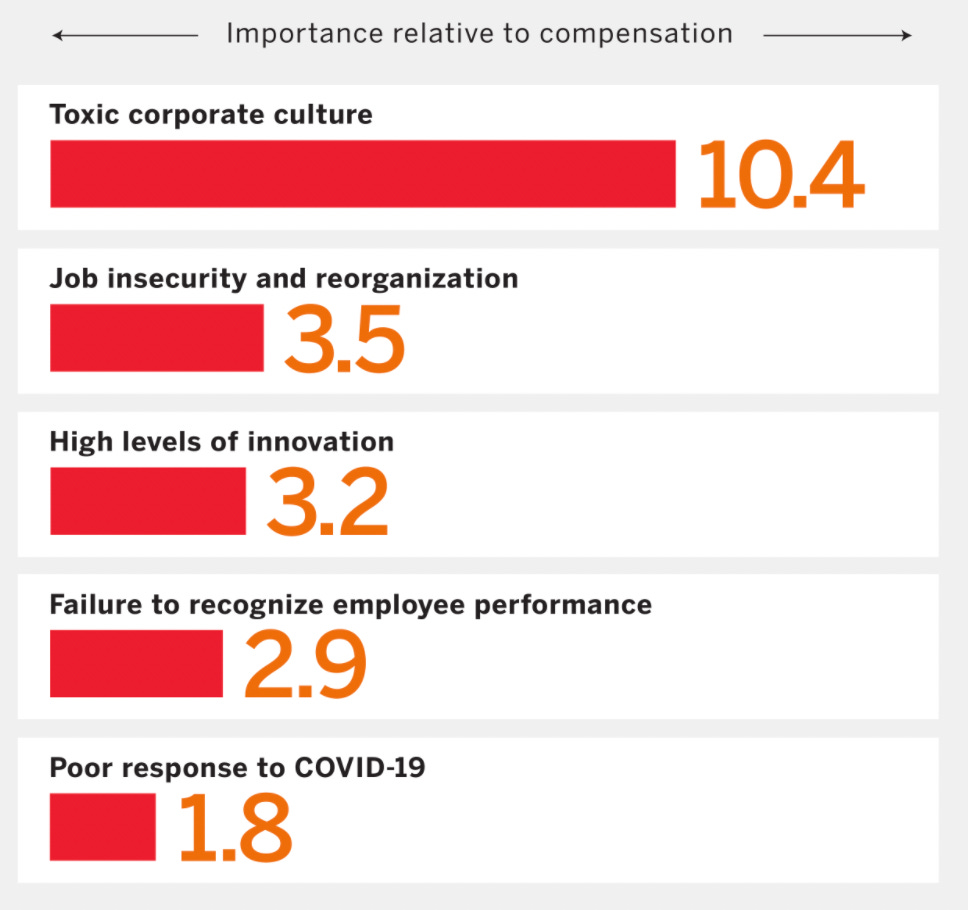

Much of the discussion of the Great Resignation has been about pay. In fact the researchers found that compensation was only the 16th most important factor. They chose to use this pay-motivated quit rate as their benchmark and then ranked other motivations alongside it.

By far the biggest reason to quit was a toxic culture - it is ten times bigger than pay as a reason for someone to leave their job.

The authors of the work said that toxic culture included a disrespect for diversity and inclusion, poor managerial treatment of workers and unethical behaviour. As the chart shows job insecurity was the next most important factor. Next, firms regarded as ‘innovative’ tended to be experienced as having intolerable levels of work intensity leading to workers quitting due to burnout.

It was also interesting to observe that employee recognition was a critical motivator. Higher performing individuals reported feeling frustrated at a lack of recognition (and when underperforming colleagues weren’t called out for their weaker contributions).

Toxic culture doesn’t just lead to employees quitting, workplace engagement for those who stay drops by twenty percent.

The authors of the study revealed something fascinating in this interview with Brene Brown. If a leader of an organisation has a drink driving conviction the organisation is 25% more likely to be caught committing fraud. Culture,integrity - and the respect for standards - comes from the top.

All of this begs the question of how to reinvent bad cultures. I decided to take a close look at a culture that rightfully is under intense scrutiny - that of the Met Police.

The suggestion that the Met Police culture is disfunctional isn’t editorialising on my behalf, this year a report from the Independent Office for Police Conduct found ‘shocking evidence of a profoundly sick force’ including calling out ‘disturbing texts between serving officers’ that were excused as ‘banter’. It was in the name of such banter that two other Met officers were caught exchanging images of victims from a murder scene - a crime that saw them both jailed at the end of 2021. It’s worth adding that it appears that the texts (received by 41 fellow police officers) weren’t reported by most of their colleagues, but a single whistleblower did eventually file an anonymous complaint that saw them investigated.

The January report by the Police Conduct office reported that while the content of the texts they had seen were ‘abhorrent’ only two officers had been fired and others had been promoted. Even the Daily Mail conceded that police leaders faced ‘tough questions for failing to eradicate the vile microclimate’ that permitted such actions. The report itself highlights the ‘ingrained dysfunctionality’ of the police culture ‘that is at best tolerated, at worst swept under the carpet’.

An independent observer might wonder if the Sarah Everard case might have precipitated a moment of reappraisal and reinvention, that the Met might have chosen to renew the terms of their relationship with the population they serve. After all a serving police officer, nicknamed The Rapist by his own colleagues had raped and murdered a young woman under the cover of having grounds to arrest her. A wise perspective might have been to allow an evening of peaceful protest as recognition that the force was listening.

Instead, while (male-dominated) anti-lockdown protesters were being permitted to create daily mayhem outside of Parliament the Met chose to aggressively shut down a women’s vigil for Everard. An intervention that a judicial decision last week declared was itself illegal, finding that the protests were legitimate and democratic.

So it begs a question that has relevance not only for the police but for all organisations.

How do you change a toxic culture? What are the steps that you need to take? This is the question we tackle in today’s podcast (summarised below if you don’t listen).

In the podcast I talk to two guests who have slightly different perspectives on how to fix the culture of the Met Police.

Dr Megan O’Neill is Associate Director at the Scottish Institute for Policing Research. She has extensively studied the police and has worked closely with them - most notably helping to revise a stop and search policy that was found to be failing. She explains the challenges of the job, and how we should think about getting buy in to reform.

Simon Holdaway is Professor emeritus of Criminology at the University of Sheffield. He joined the police after he left school and was promoted to sergeant. His study about the police has explored the culture of the profession and how themes of race could be more effectively tackled.

What comes across from the discussions is that there are four lessons relevant for cultural change in any organisation.

Space - good culture can't exist when there is no slack in the system

Voice - workers need to feel like they are heard (Megan describes a process of 'organisational justice') - this makes workers feel valued

Values - explaining what the organisation stands for is vital

Middle management - behind any culture problem there's the need to purge the organisation of cultural misfits - getting the middle management right is the best way to make this take hold