Building community isn't a mystery

ALSO: a LinkedIn post raises the fearful consequences of burnout

I chatted to an organisation a month or so ago, they wanted to know what direct actions they could take to build a sense of community between their employees. They felt that work was more transactional than ever before.

In truth, we often achieve these goals obliquely, we don’t simply press a button marked community, but rather we take a dozen actions that help indirectly serve create the climate for connection.

When I talk to companies about these things the actions can seem so mundane that they don’t seem to be the ‘big ideas’ that we’re often searching for. Quite often creating the time for colleagues to spend time together, and then letting them spend time together creates magic.

There are two critical components there. Firstly if team members have hours of back-to-back meetings, the suggestion of sitting down and having lunch together can feel insultingly tin-eared. Organisations need to be assertive about reducing the demands on colleagues time’. (The Presence deck might be helpful here).

But take a look at this research about firefighters. The more frequently they ate lunch together the more their group performance improved, eating together served to strengthen their culture and co-operation in times of high stress (major emergencies in their case) was also seen to improve.

I did some work with a major fire service recently. They told me that as diet preferences change fewer and fewer firefighters eat together. At the same time fire crews don’t feel as cohesive as they once were.

Once we know these simple practices have an impact we then might want to think about how we curate these interactions to make them happen more.

A few years ago I spoke to Ben Waber, someone who has used data to understand how to build bonds between people. In one organisation he observed there were big productivity gaps between different teams, and it was reflected in their networks in the organisation:

In one company we saw that by far the most productive people they were eating lunch with 11 other people (sometimes it was 10, or nine other people). By far the least productive people they were always eating lunch in groups of two or three other people. It was never more that. We wanted to figure out why was this happening. We go to the cafeteria and we saw what was happening. By one set of doors all the tables had 12 seats. The other set the doors all the tables had four seats.

Listen to the whole discussion with Ben.

Along the same lines, in 2022 I had a fascinating discussion with Martin Houghton-Brown, now General Secretary of the Duke of Edinburgh Award Foundation. He told a compelling story of how a table in the communal area at his previous work served to create a focal point for social interactions.

There’s a recurrent theme in these testimonials, that bigger tables seem to have more impact that smaller ones because they force conversations with people we don’t know as well (sometimes called ‘weak ties’).

I especially enjoyed this example about the role of dining tables in building a harmonious cohesion amongst the members of Graduate House, a college in Sydney. As the dean of the college explains:

At the beginning of every year, I give an introductory talk about the rules and regs and the conventions of the House, and I give it in the Refectory. There, I explain the club room rule: when you arrive at informal dinner, you have precisely no choice where or with whom you sit. Instead, you take your plate, head to the first of the long tables, and sit in the westmost open seat. Over the course of the service, the table fills up from west to east, and any gaps fill as previous diners finish and depart. No one sits at the second table unless the first is completely full. Finally, if you see anyone sitting alone at a different table, it is the responsibility of every member of the house to trot right over and sit opposite them with a beatific smile, and either eat there or drag them over to the communal table.

While this might be a superficially important rule it very quickly has an impact:

The consequence of this system is that it takes only a week or two for everyone in the House to have dined alongside nearly everyone else, and this means that the naturally intimidating task of sitting next to someone new at dinner is both undermined at the start, and entirely trivial by week three… The long table is an essential tool for rebuilding the ‘third places’ – communal places that are neither home nor the workplace – that are too often missing from people’s highly private 21st-century lives. So, if you have the opportunity to make a decision about how people will sit down together, or to influence the decision, or to complain about the decision – seize it. Reject the little tables. Embrace the long. Make every meal a banquet, and watch your community flourish.

One way to take those learnings and to apply them to your own team might turn meals into moments. Either agree to eat packed lunch together once a week, or once a month and commit to it.

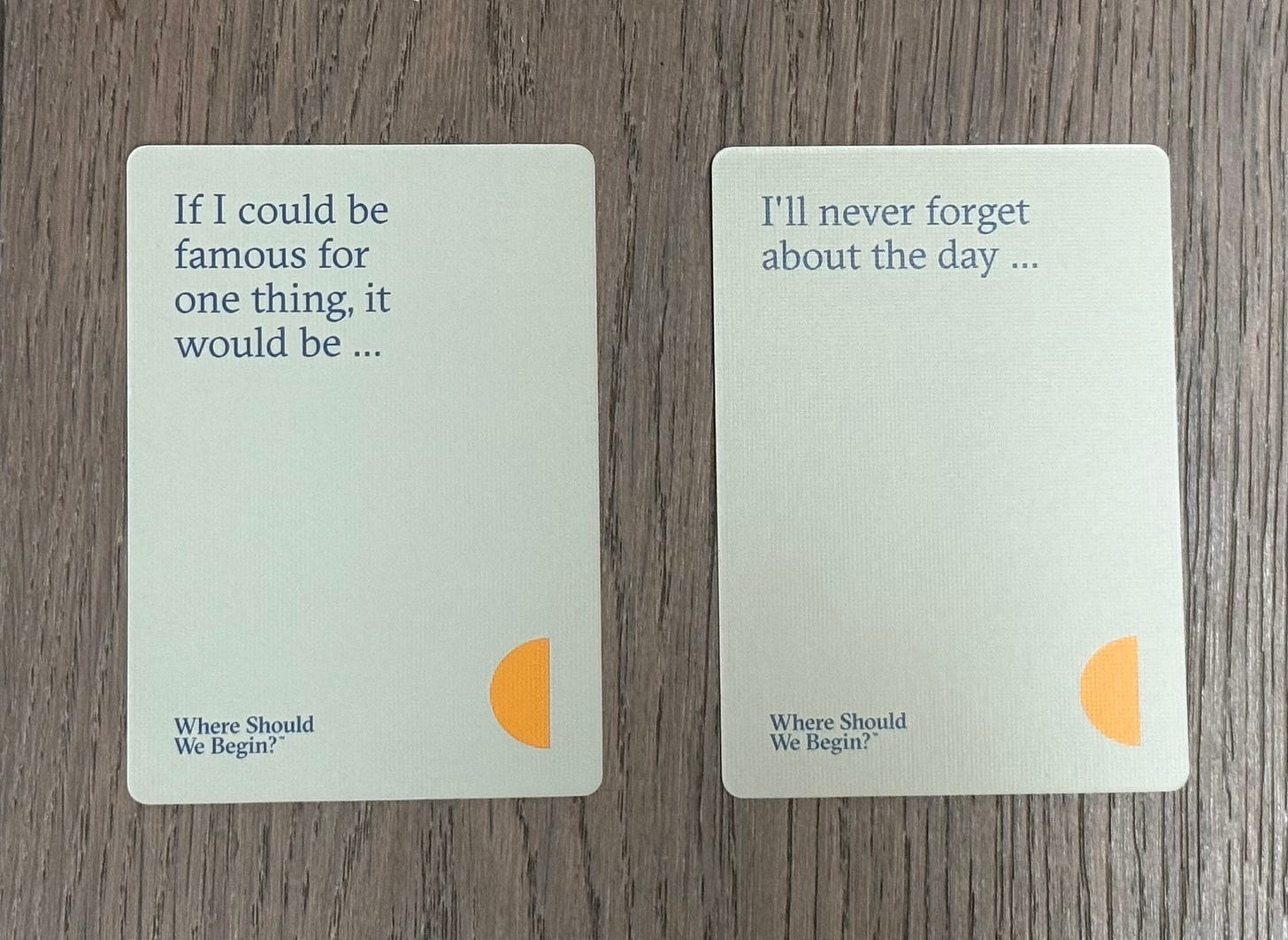

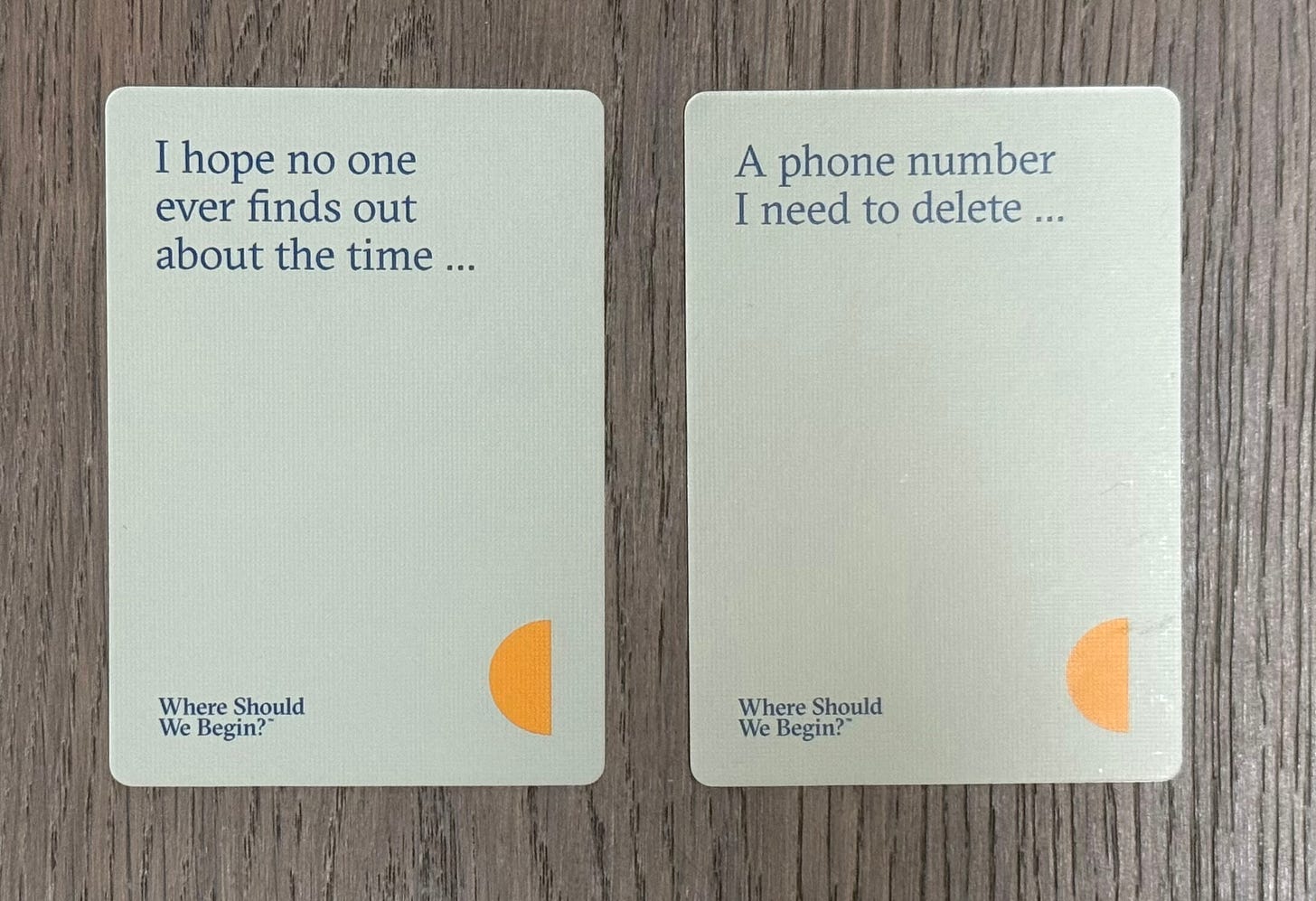

You could also take it further. A way to run a memorable bonding dinner inspired by a LinkedIn post by Dave Cairns could be to use something like Esther Perel’s ‘Where Should I Begin’ card set. It includes prompts like these:

Dave’s post shows how he used the game. We sometimes need to cross the sea of awkwardness to get to the good stuff.

All of this is a reminder that community can’t just emailed to people. It depends on building understanding and connection.

I’d love to hear what other techniques you’ve used.

"There's no single worse thing you can say to someone who is burnt out than 'Why don't you go for a walk?'"

Myself and Christine Armstrong talked about an inspirationally candid LinkedIn post by Annabelle Black - and what any of us can do to beat burn out. Watch it here.

I found this quite useful. HBR published a synthesis of what 570 experts think will happen with work and AI. (Caveat: they were all Belgian experts, because I don’t know why). Here’s the consensus of what will happen when (in Belgium at least):

2026 - Job tasks are partially automated

2029 - New technologies are creating new jobs/industries

2035 - Economic inequality increases dramatically

2037 - Humans work alongside robot colleagues

2042 - Third World War breaks out. No mention of whether Belgium are involved

2046 - Automation leads to shorter work weeks. Yes you’re merely 22 years from a four-day week

2051 - Governments around the world introduce universal basic income

2053 - Breakthroughs in longevity drastically extend the lifespan of the technocratic elite. (I think this means Zuckerberg and Musk are living forever)

2065 - Computers surpass humans on everything

2074 - Human civilisation changed irreversibly by uncontrollable superintelligence beyond our comprehension

‘There is a sense of insecurity that never leaves you if you grew up working class’ - this piece about the mindset that growing up working class gives you is worth reading

Have you played around with Google’s Notebook LM? It allows you to upload your own content and then ask an AI to answer questions based on it. I uploaded 10 of the best recent episodes of Eat Sleep Work Repeat and asked it to create a podcast based on it. Slightly meta (a podcast about a podcast). I don’t agree with all of what it claims to have summarised but it’s interesting. Listen here:

Really disagree about the "Where should I begin cards". I instinctively find these kind of things intrusive and deeply uncomfortable. My first answer to things like 'What would you be famous for' is actually deeply personal. So being asked questions like that at work is a case of searching for suitable bland substitute answers, making me feel anxious and defensive.

Big fan of the question cards at dinner. The school of life questions for conversations are great for this