3 Workplace Culture Mistakes of Elon Musk

ALSO: new data raises the question, is hybrid killing worker productivity?

Elon Musk has brought some serious Liz Truss on a hen weekend energy to his newly minted ownership of Twitter.com.

Firstly some context, I tend not to talk about it here (or on the Eat Sleep Work Repeat podcast) but I worked for Twitter for eight years from 2012 to 2020. Initially I helped to build the UK team then evolved to a leadership role across Europe, Middle East and Africa. It was most decidedly not exclusively down to me but the culture of the London office was famed throughout the business. It was also the best performing large office in the internal ‘pulse’ surveys.

It was when the culture went wrong (after a second round of global job cuts around 2015-16) that I started my podcast. At the time it was partly an act of rebellious subversion against what I saw as misguided global decision making, and partly it was an attempt to learn what I was doing wrong myself. As a few people have asked my perspective here are what I think are Elon Musk’s workplace culture mistakes from his first 12 days in the firm.

I have no doubt that Elon Musk is a formidably successful businessman, using his earnings from PayPal to acquire Tesla and to help him win a major NASA contract to set up Space X. But that doesn’t make him immune to making mistakes with Twitter and his behaviour since he first mooted buying the firm has been chaotically unpredictable.

Rather than just list the mishaps during the course of doing the on again/off again deal, I just wanted to discuss Musk’s workplace errors since he has taken over the social media platform. This isn’t just errors of judgment like firing people and then asking them to come back, but mistakes that damaged the culture. I initially had a list of 5 mistakes, but for brevity here are three of them.

3 Work Culture Mistakes of Elon Musk

Killed psychological safety at birth

Filled an explanation void with crass behaviour

Turned culture into ‘them’ and ‘us’

I’ll talk through each of these after this ad.

====================== AD FEATURE ======================

Per Diem is a different kind of online store, selling the top fifty most boring things to shop for - pasta, olive oil, rice, soap, cleaning things and so on. Sourced from amazing indie suppliers, delivered plastic free in monthly batches and really well priced. Check it out here - https://www.getperdiem.com/

======================================================

1. Killed psychological safety at birth

One of Musk’s first acts was to order Twitter’s development team to ship a new feature of paid-for-verification within 10 days. If the team couldn’t hit the deadline Musk said he would fire them.

Communicating an urgent deadline isn’t inappropriate, leaders sometimes want to signal that the company is on a wartime footing rather than having the breathing space of peacetime. But getting workers to walk the gangplank, telling them that their mortgage payments are dependent on them getting the job done is a surefire way to destroy psychological safety.

Many of us are familiar with the VW Dieselgate affair where the German car maker had set their sights on becoming the biggest car manufacturer in the world. To do that they needed to sell more diesel cars in the US. One of the major hurdles in front of them was to improve their engines to pass the exacting cleanliness standards that were being implemented in states like California. To overcome this challenge pressured VW engineers hatched a duplicitous solution. When the car was in ‘test mode’ the engine would go into gloriously low emissions operation that allowed it to skip through any tests. Once the car was unhooked from an exhaust pipe measurement it would revert to burping out its standard noxious output. When the affair came to light CEO Martin Winterkorn quickly resigned in disgrace. The cost of Dieselgate was estimated to be around $35 billion and it continues to cast a shadow over the brand’s reputation.

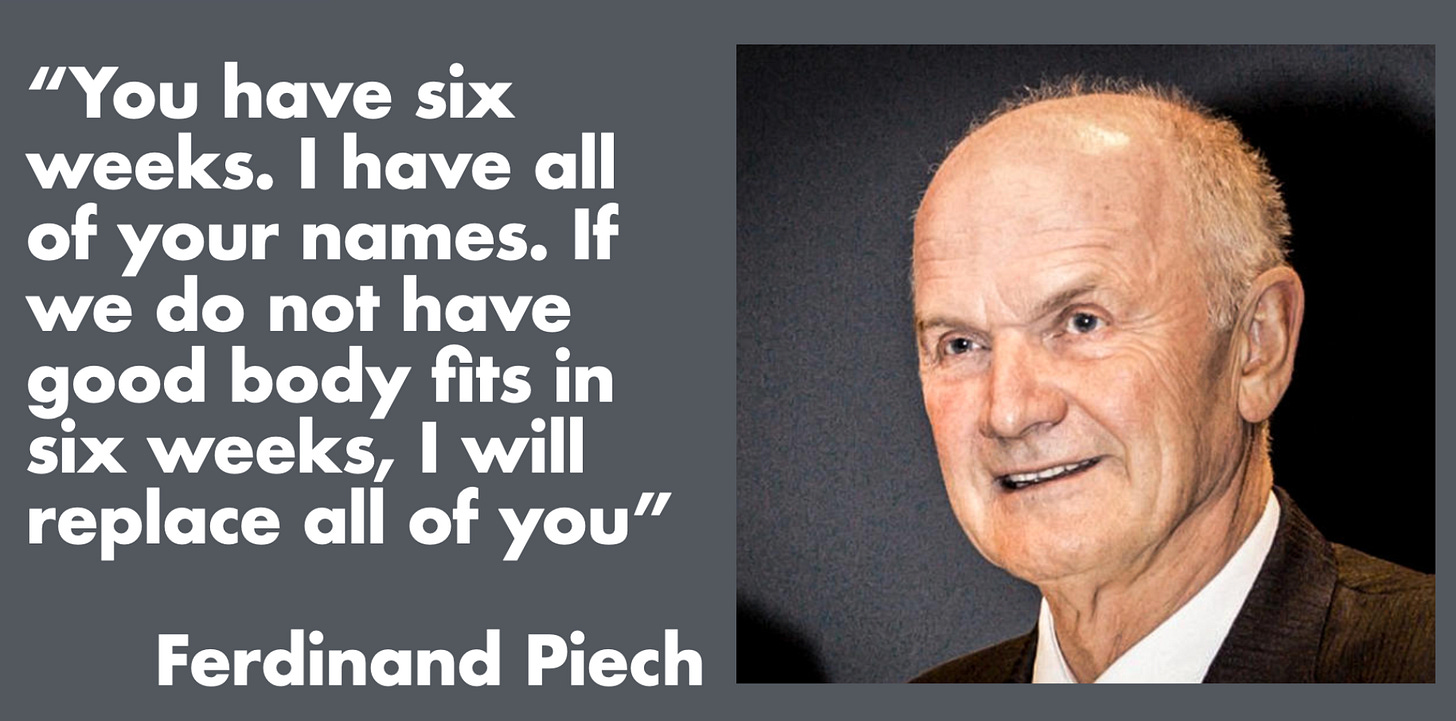

Psychologist Amy Edmondson delved deep into the culture at VW in her book The Fearless Organisation. She said that there had been a long-standing climate of bullying at the firm that led workers to make decisions out of fear. Edmondson cites a story of a previous episode under the leadership of the Winterkorn’s predecessor Ferdinand Piech. Piech had been furious about the quality of bodywork on a new model and is reported to have shouted at the gathered engineering team: ‘You have six weeks. I have all of your names. If we do not have good body fits in six weeks, I will replace all of you'.

Visualise being confronted with such a threat. If the solution is in your control then you can focus and get it done, but if the demand is impossible it invites workers to start anxious improvisation. Edmondson observed that a culture of intimidation and fear doesn’t produce better results, it merely invites employees to speculate how they can achieve the unachievable by other means. In the case of Dieselgate the engineering team couldn’t easily make the diesel engine cleaner, so they focussed on performing what they were instructed: ‘make sure we pass these tests’.

Telling workers they will be fired if they fail to achieve a goal can not only invite teams to cut corners or to make slapdash compromises, but it also signals that doing your best work isn’t good enough. At any moment you could lose your job and jeopardise your livelihood on the whim of an unpredictable leader. Ultimately most of us don’t want to negotiate with terrorists, let alone work for them.

2. Filled an explanation void with crass behaviour

As I write this media is reporting that Musk still hasn’t addressed Twitter employees since he bought the firm 12 days ago. His first act on taking over at the firm was to walk into the offices carrying a sink. (‘Let that sink in!’ he joshed, the week before firing half of the workforce). While half of the company was being dismissed on Friday morning he was exchanging jokey tweets with someone who was speculating that he was an alien.

Most of us who have worked through the length of an economic cycle recognise that there are times when companies need to let workers go. Whether because of their own actions or because of the performance of the organisation it’s an unnerving thing for an individual to be told they are losing their job. But there is a way to do this with grace. The important consideration is to recognise that most workers who are leaving don’t care about reasons - they just want to know what the decision means for them. Typically when preparing to lay off workers leaders are told that those losing their jobs won’t take in anything after discovering the decision. Managers are instructed to provide the information in back-up form afterwards. But for those being asked to stay explanation is vital. A leader’s role is to be a storyteller, to provide narrative and clarify about where the organisation is heading. To paint a picture of what lies ahead.

But Musk, who in the last fortnight has found time to endorse the Republican party, egregiously slander the husband of Speaker Nancy Pelosi and permanently ban comedians who choose to impersonate him on the platform, still hasn’t talked to his employees.

Twitter employees told Casey Newton ‘that they had been struck by the cruelty: of ordering people to work around the clock for a week, never speaking to them, then firing them in the middle of the night, no matter what it might mean for an employee’s pregnancy or work visa or basic emotional state’. The fact that the job cut email wasn’t signed, merely coming from ‘Twitter’ added to the savagely impersonal approach.

Jobs cuts are never easy but organisations like Stripe and Airbnb have implemented them with grace. Team members who remain are looking to answer a simple question - am I making a good decision by staying here? Do I trust the vision being laid out for the organisation? For Musk, staying absolutely silent, while behaving like a obnoxious teenager in public, is likely to lose the loyalty of those who have been retained.

3. Resilient culture has a clear sense that ‘we’re all in it together’

Great cultures - whether in organisations or even when we consider groups like the people of Ukraine, are resilient when they have a cohesive sense that ‘we’re all in it together’. That sense of 'we-ness’ is protective, but can also find itself focussed in opposition to outgroups. We’re all familiar with the idea of ‘us’ vs ‘them’ arguments. It’s certainly possible to frame Boris Johnson’s downfall by recognising that when he was booed at the Queen’s Jubilee it was because he’d ceased being viewed as ‘one of us’ (by his supporters) but was now being perceived as ‘one of them’. Groups can be mobilised by sharing a common cause, or even by having a common enemy, but it’s a dangerous place to be on the wrong side of the people you employ.

Liverpool manager Jurgen Klopp has always had a visceral understand of strong culture. According to his biographer Raphael Honigstein, when Klopp was the manager of the German Bundesliga side Borussia Dortmund, he made it clear to everyone in executive roles at the club that they ‘had to develop this feeling of “we”’.

In Klopp’s mind the mentality of players had to move from ‘me’ to ‘we’. The manager clearly intuits how important cohesiveness is for good culture. At the start of the Covid pandemic, professional football was challenged by what to do about what was left of the 2019-2020 season. There was a genuine fear that suspension of the league would lead to the season being abandoned.

Klopp’s acceptance of the decision to suspend matches during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, even though it involved a threat to Liverpool’s title run in the Premier League, was magnanimous. On 13 March 2020 he released a statement explaining his simple reasoning: ‘if it’s a choice between football and the good of wider society, it’s no contest.’ It was a far cry from the famous words of a former Liverpool manager, Bill Shankly: ‘Some people think football is a matter of life and death. I assure you, it’s much more serious than that.’

In Klopp’s 381-word statement Klopp used the words ‘we’, ‘us’ and ‘our’ seventeen times:

Psychologist Alex Haslam explains that ‘For leaders this sense of us-ness is the key resource that they need to marshal in order to secure the support and toil of others’.

Musk has spent no time trying to develop a sense of ‘us’ with his remaining employees. Indeed if anything he seems intent on trying to encourage them to leave. Good culture requires a strong sense of cohesion. Musk needs to set about cultivating it as a matter of urgency.

This podcast discussion between Dr Rangan Chatterjee and David Hamilton is dazzlingly good. We’re all familiar with the idea of a control group in drug tests because required just believing that something will work in itself creates a healing effect. But we throw that part away as a given and don’t spend time asking why. Hamilton asks can we have more of that belief part?

The Washington Post published an article on falling workplace productivity that turned a few heads because of the fall shown in 2022’s data. (Article free to read on this link). (Is remote work causing a productivity dip? Professor Nick Bloom says no…)

The importance of touch is often a sensitive topic to bring to workplace discussion. Alarming #MeToo discourse about male leaders offering ‘special cuddles’ has made the idea of any physical contact in the workplace seem taboo. But touch is a vital human signal, this article from The Psychologist reminds us that touching someone’s arm is one of the most intuitively understood of human interactions - with many different meanings.